In the previous post, I discussed the publication of the first Greek New Testament compiled by Desiderius Erasmus in 1516, and some notable aspects of its history. But what made the few Greek manuscripts in existence at the time any more legitimate than the Latin ones of the Vulgate? The idea that

Greek manuscripts were more reliable than the Latin ones was a

preposterous notion in the 15th and early 16th centuries, but the Dutch Humanist posed the question:

"How is it that Jerome [c.347-420 AD, translator and compiler of the original Vulgate], Augustine, and Ambrose all cite a text which differs from the [current] Vulgate? How is it that Jerome finds fault with and corrects many readings which we find in the Vulgate? What can you make of all this concurrent evidence - when the Greek versions differ from the Vulgate, when Jerome cites the text, according to the Greek versions, when the oldest Latin versions [Vetus Latina] do the same, when this reading suits the sense much better than that of the Vulgate - will you, treating all this with contempt, follow a version corrupted by some copyists?"

Erasmus also recognised that Latin was on the decline, and to hide the secrets of God's Holy Word away in a language known only to a few was a travesty. Many laymen heard short passages of the Vulgate during the mass - together with the usual orthodox interpretation - but there was no freedom to fully comprehend the intricacies of God's Word in the vernacular. While he did not personally engage in translating the Bible into any vernacular languages, Erasmus encouraged those brave individuals who did so, via his books and private letters. By the early years of the English Reformation, his Bible paraphrases and commentaries were translated into English and placed alongside the Bible in every church in England. In the preface to one of the editions of his Novum Testamentum, the scholar wrote:

"I wish that even the weakest woman should read the Gospel – should read the epistles of Paul. And I wish these were translated into all languages, so that they might be read and understood, not only by the Scots and Irishmen, but also by Turks and Saracens. To make them understood is surely the first step. It may be that they might be ridiculed by many, but some would take them to heart. I long that the husbandman should sing portions of them to himself as he follows the plough, that the weaver should hum them to the tune of his shuttle, that the traveller should beguile with their stories the tedium of his journey."

Those sentences in the middle regarding translating the Bible stand out to me the most: "To make them understood is surely the first step. It may be that they might be ridiculed by many, but some would take them to heart."

Of course there will always be men and women that shun the Bible, and (as the Catholic Church in the Middle Ages feared,) poke fun at it in taverns, inns, meeting halls, marketplaces, and in their private chambers. However, that is between them and the Lord, and the fact is that some of those men and women will hear and read the truth, and the truth will set them free. It is a personal decision that cannot be forced, nor denied by any group on earth. For that reason the Lollards spread the Gospel and gave their handwritten Middle English manuscripts to the laity; and it is for that reason Erasmus's writings inspired William Tyndale, Martin Luther, and others to translate the Greek and Hebrew testaments into the languages of their people, so that all may be able to choose to make their own personal conscious decision for Christ.

Quote sources: How Our Bible Came To Us by H.G.G. Herklots

Wednesday, February 19, 2014

Monday, February 3, 2014

Source Manuscripts of Erasmus's Greek New Testament

Here's some information I have reprinted from a previous blog of mine:

In 1516, Desiderius Erasmus published Novum Istrumentum Omne - the first printed Greek New Testament, and perhaps the crowning achievement of the Dutch Catholic Humanist's life. At the behest of printer Johann Froben, the work was rushed out, in competition with Cardinal Francisco Ximenez' Complutensian Polyglot, and was unfortunately riddled with printing and translation errors.

Despite issues, the tome was well received by the academic community, but scorned by many ecclesiastical authorities, citing its many departures from Latin Vulgate. Erasmus claimed that his goal in the creation of his 'New Instrument' was to revive critical interest in the Bible, whose dated 4th century Latin should updated to its original language of Greek (with a translation into Classical Latin placed alongside). Long-venerated, only recently have historians been able to examine just where much of the text originated.

Most King James Version Only'ist websites state that Erasmus (who gave us the base text of the King James Version,) used "the best manuscripts in European libraries" for his Novum Instrumentum. Research has shown that this assertion is debatable. Historian W.W. Combs, in his article "Erasmus and the Textus Receptus" (Spring 1996 Detroit Baptist Seminary Journal) asserts that Erasmus only borrowed seven manuscripts altogether, all from the Dominican library in Basel, Switzerland. None were the complete New Testament, and all were relatively young in age:

*Name, content, date.*

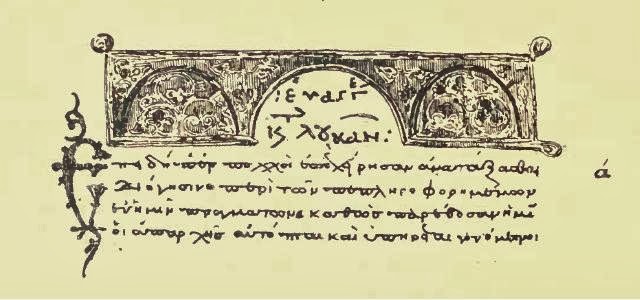

Codex 1eap (entire New Testament except Revelation, 12th century, pic above)

Codex 1rK (book of Revelation, 12th century)

Codex 2e (Gospels, 12th century)

Codex 2ap (Acts and Epistles, 12th century)

Codex 4ap (Pauline Epistles, 12th century)

Codex 7p (Pauline Epistles, 12th century)

Codex 817 (Gospels, 15th century)

The origins of all seven of these manuscripts cannot be fully deduced, but there are a handful of records that point to a few. John of Ragusa, a Dominican friar who visited Basel for one of the church councils in 1431, reportedly gifted three manuscripts to the Dominican convent at which he had lodged. Two more codices may have been on loan from the library at St. Paul's. The rest had likely been in collection at Basel for some time.

When Codex 1r (and possibly others) was missing sections, Erasmus lifted those passages from the Latin Vulgate, translated them into Greek, and inserted them into his text. This is a hotly contested choice even today, and is the source of much contention between the KJVOnlyists and the Anti-KJVOnlyists. In any case, Erasmus heavily edited his work, and subsequent editions were far more solid. Notably, the 2nd edition was used by Martin Luther in translating his 1522 German New Testament, and the 3rd edition was used by William Tyndale in his 1526 English New Testament (whose text survived despite heavy Catholic persecution, and 80% of which was carried over into the KJV's New Testament). The 3rd, 4th, and 5th editions were utilised in Robert Estienne's 1551 Editio Regia - the Textus Receptus that would serve as the primary Greek New Testament source for the next several hundred years.

In 1516, Desiderius Erasmus published Novum Istrumentum Omne - the first printed Greek New Testament, and perhaps the crowning achievement of the Dutch Catholic Humanist's life. At the behest of printer Johann Froben, the work was rushed out, in competition with Cardinal Francisco Ximenez' Complutensian Polyglot, and was unfortunately riddled with printing and translation errors.

Despite issues, the tome was well received by the academic community, but scorned by many ecclesiastical authorities, citing its many departures from Latin Vulgate. Erasmus claimed that his goal in the creation of his 'New Instrument' was to revive critical interest in the Bible, whose dated 4th century Latin should updated to its original language of Greek (with a translation into Classical Latin placed alongside). Long-venerated, only recently have historians been able to examine just where much of the text originated.

Most King James Version Only'ist websites state that Erasmus (who gave us the base text of the King James Version,) used "the best manuscripts in European libraries" for his Novum Instrumentum. Research has shown that this assertion is debatable. Historian W.W. Combs, in his article "Erasmus and the Textus Receptus" (Spring 1996 Detroit Baptist Seminary Journal) asserts that Erasmus only borrowed seven manuscripts altogether, all from the Dominican library in Basel, Switzerland. None were the complete New Testament, and all were relatively young in age:

*Name, content, date.*

Codex 1eap (entire New Testament except Revelation, 12th century, pic above)

Codex 1rK (book of Revelation, 12th century)

Codex 2e (Gospels, 12th century)

Codex 2ap (Acts and Epistles, 12th century)

Codex 4ap (Pauline Epistles, 12th century)

Codex 7p (Pauline Epistles, 12th century)

Codex 817 (Gospels, 15th century)

The origins of all seven of these manuscripts cannot be fully deduced, but there are a handful of records that point to a few. John of Ragusa, a Dominican friar who visited Basel for one of the church councils in 1431, reportedly gifted three manuscripts to the Dominican convent at which he had lodged. Two more codices may have been on loan from the library at St. Paul's. The rest had likely been in collection at Basel for some time.

When Codex 1r (and possibly others) was missing sections, Erasmus lifted those passages from the Latin Vulgate, translated them into Greek, and inserted them into his text. This is a hotly contested choice even today, and is the source of much contention between the KJVOnlyists and the Anti-KJVOnlyists. In any case, Erasmus heavily edited his work, and subsequent editions were far more solid. Notably, the 2nd edition was used by Martin Luther in translating his 1522 German New Testament, and the 3rd edition was used by William Tyndale in his 1526 English New Testament (whose text survived despite heavy Catholic persecution, and 80% of which was carried over into the KJV's New Testament). The 3rd, 4th, and 5th editions were utilised in Robert Estienne's 1551 Editio Regia - the Textus Receptus that would serve as the primary Greek New Testament source for the next several hundred years.

Sunday, February 2, 2014

Layout of Bible Codices

Back when early codices were being copied down, there

was no such thing as printing (obviously), so all scripture was in

hand-written manuscript form. In order to save supplies and to make the tedious process of copying scripture go faster, no divisions were placed in the

text — there were no spaces between words or sentences. Some "holy

words" were even abbreviated, since they were repeated often. There were no chapter and verse divisions at all, just long lines of text. You can find photographs of this in many manuscripts prior to the Medieval period, evident in such texts as the Codex Alexandrinus, Amiatinus, Sinaiticus, and many others.

Scripture typically looked like the text here, taken from Acts chapter 2. As a note, our current chapter divisions were not put in until 1205 AD, under the supervision of Archbishop of Canterbury Stephen Langton. Modern verse divisions were first inserted by Robert Estienne (aka Stephanus) in the 1551 edition of his Greek New Testament.

I personally exhort fellow Christians to find a Bible that does not have any verse divisions and read through a gospel or letter in one sitting; this is the way they were 'meant' to be read, and I often get more out of those books than I do when I just read a short passage. There's not many editions like this out there, but their number is increasing.

Some Bibles without verse divisions:

- The Reader's Digest Condensed Bible (RSV)

- ESV Reader's Bible

- The Books of the Bible (NIV 2011)

- Any historical facsimile of a Bible version from the mid-1500s or prior.

Scripture typically looked like the text here, taken from Acts chapter 2. As a note, our current chapter divisions were not put in until 1205 AD, under the supervision of Archbishop of Canterbury Stephen Langton. Modern verse divisions were first inserted by Robert Estienne (aka Stephanus) in the 1551 edition of his Greek New Testament.

I personally exhort fellow Christians to find a Bible that does not have any verse divisions and read through a gospel or letter in one sitting; this is the way they were 'meant' to be read, and I often get more out of those books than I do when I just read a short passage. There's not many editions like this out there, but their number is increasing.

Some Bibles without verse divisions:

- The Reader's Digest Condensed Bible (RSV)

- ESV Reader's Bible

- The Books of the Bible (NIV 2011)

- Any historical facsimile of a Bible version from the mid-1500s or prior.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)